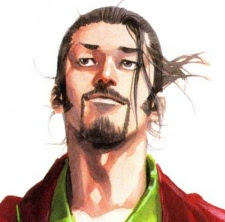

By all accounts, Hon’iden Matahachi had made nothing of himself. After fleeing the battle of Sekigahara with his friend, Shimmen Takezo (who later became the legendary undefeated samurai known as Miyamoto Musashi), Matahachi abandoned the fiancé waiting for him back home in favor of being “kept” by an older widow who had piqued his lust and kept him steeped in sake. During the prime of his life, while his boyhood friend was traveling the country applying himself earnestly to learning the sword, Matahachi passed his days, year after year, drunk and indolent, utterly dependent upon the widow for his every need.

Both Matahachi and Musashi were young and idealistic. They both desperately wanted to be known for something, to make a name for themselves in the world at large. To this end, Musashi applied himself single-mindedly toward mastery of the sword. He roamed the country, challenging any and all who claimed to be masters of the Art of War. His training consumed his mind, body, and spirit. He took for his teachers the entire natural world – the rocks, the rivers, and the mountains were equal in their importance to his lessons as combatant samurai. He dedicated everything he experienced, every waking thought, to the pursuit of mastery.

Matahachi lingered. In his mind, he was destined for great things, but his actions were frozen in place. Eventually, he did leave the widow. Stealing off in the night, he set out to regain his honor and right the course of his life.

One day, while working as a day laborer in Fushimi castle, he witnessed the death of a traveling warrior, who had been accused of being a spy. Before the castle guard could descend upon the body, Matahachi retrieved the personal belongings of the dead man and spirited away with them. His original intentions were noble: he wanted to return them to the family of the man who had died.

Upon inspecting the man’s belongings, Matahachi found a certificate from a legendary sword master bestowing upon the recipient the rank of master of the Shujo sword style. Matahachi assumed the man who had died was the man to whom the certificate was addressed.

Later, after some twists and turns of fate, Matahachi met a traveling warrior at a sake shop who boasted to him of all the big-name samurai he knew. Feeling the need to impress this man, Matahachi claimed to be the dead man, master of the Shujo sword style, Sasaki Kojiro.

In Matahachi’s mind, there was no real problem with this. The man was dead, after all, and the certificate he carried vouched for him as an expert swordsman. The chasm that separates the expert – someone who had done the work to attain mastery – and the charlatan seemed to him the matter of a simple white lie. He was, after all, destined for great things, and with this man’s credentials he could score a position which better reflected his station (as he understood it).

This story comes from the classic Japanese historical fiction Musashi by Eiji Yoshikawa. Reading this, I was struck by how much of my life I have lived as a Matahachi. Big dreams, big potential, big ego, little coordinated effort.

While I have done many things, found many ways to pass my time running here and there after this diversion and that distraction, I haven’t had the focus it takes to become singularly good at something. And for that, I have become the proverbial jack-of-all-trades: conversant in much, fluent in none.

Now, I court the clarity to live my life as a Musashi or a Kojiro, to channel my energy with singular focus for the sake of the Art. And all my life will become singular with it.

Accompanied by self-proclaimed disciple Shinpachi Shimura, the strange Kagura and a giant dog named Sadaharu, Gintoki and his crew go on crazy adventures, earning money to get by in their own way. This manga is one of a kind in many ways, but what should you do when you’re all caught up on Gintama?

This was a well-written piece!

I think most people are “matahachi.” We all want great things, but we do not want to put in the hours of works or we fall to some vice like alchohol, TV, etc.

The book, The War of Art by Steven Pressfield makes a good distinction between the professional Musashi and the amateur Matahachi.